Roses and Hydrangea teach the lesson

Don't leave that thin, spindly

stuff!

- Mr. Kissinger to John Macunovich,

thence to Janet -

If part of a rose or shrub grew poorly last year, don't expect

it to somehow produce bigger and better this year. Plants grow in

much more regimented fashion -- every limb produces branches a bit

smaller than itself.

So cut back to stout, healthy wood, even if that means cutting

'way back to the base.

See it applied to roses or to mophead Hydrangea (blue or pink) with a side

lesson in Hydrangeas that refuse to

bloom.

This article is Sponsored by:

Roses excel when cut hard

Here we prune two roses, one grown as a rambler (shrubby in form

but able to reach high and appreciative of support against a

trellis at its extremities) and a typical climbing rose (with very

long, relatively weak canes that require support to prevent

sprawling).

To prune a rambler rose:

1) Cut out all weak and damaged canes. Remove them right at the

base of the plant or clip them back to a main branch, leaving a

stub if it's husky and undamaged.

2) Shorten the remaining canes.

Below: Before and after pruning. Blue arrows mark weak- and

damaged canes. Yellow arrows indicate how low we cut to remove

those weaklings.

Below: Several weeks later as spring commences in

earnest.

Prune a climbing rose:

1) Cut out all weak and damaged canes. Remove them right at the

base of the plant or clip them back to a main branch, leaving a

stub if it's husky and undamaged.

2) Identify the main canes, those you trained to fan across the

trellis or wrap up a post. Shorten them to allow new strong growth

at the tip and encourage more "breaks" (new side branches, the

places where flowers will be borne). If a main cane is growing

vertically, look for a way to lower it toward horizontal or create

more horizontal sections by winding them around a post, spiral

fashion them. Vertical canes tend to have breaks and blooms only at

the top; canes growing more horizontally develop more breaks and

flowers all along their length.

3) Think about the future. If a main cane is becoming old and

less productive, leave a new basal shoot to grow so you can train

it in next year when you remove the old cane.

Below: Husky shoots emerge from the canes we left in place.

These side shoots are what will bear the flowers.

To see other rose cutbacks: Knockout rose, miniature climbing rose, heirloom climbing rose, old

rose/shrub rose, and summer pruning of various roses.

Blue Hydrangea

digs discipline

My hydrangeas bloom but they flop

unless I stake them!

- July chorus -

We've bred Hydrangea varieties for such massive blooms

that only the sturdiest stems can support them. Your best bet is to

thin the shrub each year to stout wood. This has the additional

effect of keeping the plant shorter than it would otherwise be -- 3

or 4 feet tall rather than 5 feet or more.

Here's what we do to blue mophead Hydrangea. (H.

macrophylla varieties and hybrids, blue or pink blooms in mid-

to late summer.)

1) In early spring, cut out all weak canes. Clip them right to

the ground.

2) Cut out the oldest canes -- those most woody and most

branched. (These will produce flowers only on side branches thinner

than themselves.)

3) Thin more as needed to allow each cane room to develop leaves

right to its base.

Below: A hedge of blue Hydrangea before (left),

during (right) and after (lower left) our cut. Most wood that

remains is stout and unbranched.

Above, right: Comparing the three types of canes

involved.

The catch: Hydrangeas that

refuse to bloom

Some people say: "I pruned it this way, I pruned it that way,

and it didn't bloom either way!"

Check the tip bud in spring to learn the story.

Hydrangea macrophylla and H. serrata -- all of

the blue- and pink blooming varieties, whether ball-shaped or

lace-cap in bloom -- need more than one season to produce a flower.

(This is quite different from the white snowball- and panicle

species, H. arborescens including Annabelle' and H.

paniculata including PeeGee', which bloom on brand new

wood.)

The tip bud on a blue- or pink-blooming Hydrangea

branch must prepare itself in year one and survive to year two or

that branch will not bloom. In some regions, including the North

American midsection, these shrubs are hardy in their roots but the

tips do not survive. Those plants live but never or rarely bloom

after their planting year.

You can know if you have summer bloom coming in spring, by

checking for signs of life and vigor -- plumpness, moisture and

color.

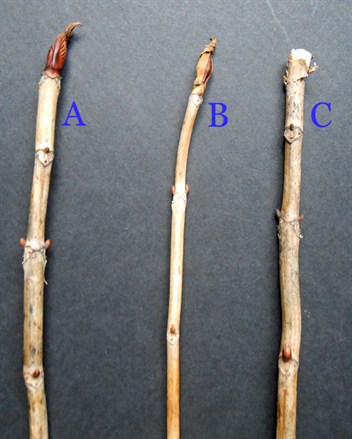

Below: A is lively and moist, B is drier, shrunken, and C

has no chance to bloom since a deer nipped the bud clean off during

winter. (Don't be hard on the deer. Sometimes the gardener is the

one who makes the mistake of pruning it off.)

Below, a cutaway view of Bud A (left) and B (right): Cut the

bud to see the story. Bud A is in good shape; now if it can simply

avoid being killed by a spring frost once it begins growing, it's a

shoo-in to bloom. The brown rotted portions in B are winter damage

-- the cells burst and died there.

Below: Buds from the examples we showed being pruned in this

article -- Cape Cod Hydrangeas. They grow in a long-fall,

moist winter climate very conducive to keeping tip buds alive. Not

only did these buds survive winter but once they begin growing in

spring they are only rarely threatened by late spring

frosts.

Sponsored by

Seal

Click to an interactive list of articles recommended by our

Sponsors.